Most Billericay townspeople know that in 1381 there occurred the Battle of Norsey Wood, the last act of the Peasants’ Revolt; few know any details. The little that is known comes from the Westminster Chronicle, attributed to Robert of Reading, and the Historia Anglicana of Thomas Walsingham.1

By the time the battle occurred, the Peasants’ Revolt was all but over. Wat Tyler,2 the Revolt’s leader, had been killed, King Richard II had reneged on all his promises and assurances to the people, and the king’s armies were mopping up the pockets of resistance in the shires. The Essex rebels were not prepared to give up their struggle without one final effort. They sent out a summons for a general mobilization at Galleywood and Rettendon Commons (6 miles north and 7½ miles east of Billericay, respectively), threatening that every able-bodied man not attending would have his house burnt down. Over the next two days messengers covered the entire county, church bells pealed, fires were lit, and men marched to the assembly points, gathering horses and tools on the way. The Rettendon group approached Billericay through the gap between Norsey Wood and Forty Acres Wood (now Forty Acre Plantation). From there they would have a clear view of Stock Hill and could await the arrival of the Galleywood group descending it. On 27th June 1381 the mobilized peasant armies met and made camp. Perhaps there were as many as 5,000 in total. The records state that the men of Essex chose to make their stand adjacent to a wood north-east of Billericay. At that time Norsey Wood extended right up to Norsey Road, the track of the roadway was atop the Deerbank, traces of which can still be seen on either side of the present road (though it is fast disappearing at the hands of developers).

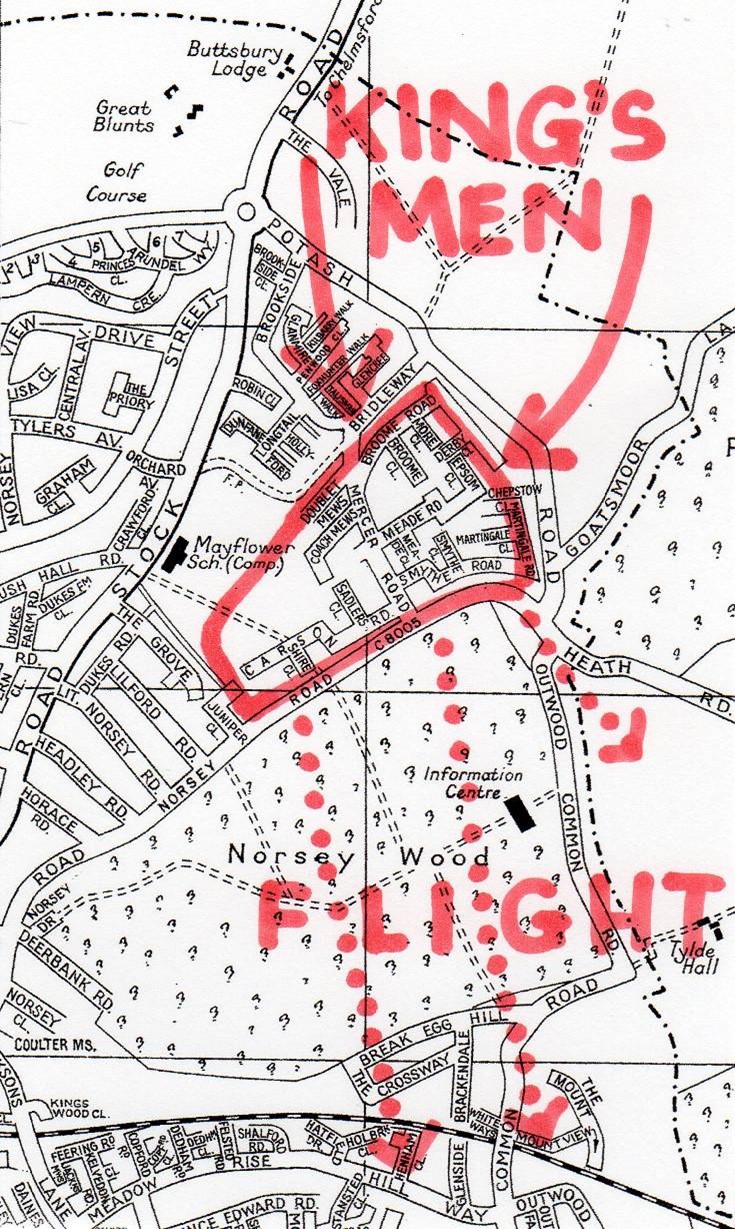

The peasants’ encampment and the site of the Battle of Norsey Wood is likely to have been in the area of the present Norsey Farm Estate backing on to the land between Norsey Wood and Forty Acre Plantation/Potash Road, although many of the peasants would have been hunted down afterwards in Norsey Wood and beyond. Their camp had the wood and its Deerbank at its rear. At that time the wedge of rough uneven scrubland between Goatsmoor Lane and Potash Road extended on the other side of the latter as far as a field boundary, a tree-lined ditch, along the present rear of the gardens of Martingale Road (even numbers). The south-west bank of the ditch was higher than the north-east bank (and still is where extant) and would have provided a natural defensive line along the camp’s the north-east side. The camp’s long north-west side would have been provided with another natural defensive line – the sunken bridleway that existed before the modern road (Bridleway) was constructed in the 1970s but still exists in part as a footpath-bridleway. This line extended as far as a second area of rough scrubland which existed at the end of Mayflower School field adjacent to Juniper Close. Along the edge of that scrubland ran the camp’s south-west edge. Thus the encampment’s sides could not easily be approached by mounted knights and it had a clear view to the north-west – the heights of Stock and Buttsbury – from which direction the attack was expected. It is more than probable that the already-in-existence Deerbank along Norsey Road formed part of the peasants’ defensive formation as a barrier from which any retreat or flight might be defended. There was even a possible escape route left open: the gap between Norsey Wood and Forty Acre Plantation.

The rebels were not militarily-minded. Their only defensive measures apart from exploiting the natural topography were to dig ditches on the flanks of the camp, to chain carts together, and to cut and place stakes in the earth as their fathers had done at Crécy. Their few real weapons – bows and rusted daggers – were supplemented by scythes, sickles and staves. They stayed round their camp-fires, raging against injustice in their lilting Essex accents, and waited through the night determined to stay in the field to defend their new-won freedoms. They did not even bother to post sentries. Just before dawn on Friday 28th June 1381 a well-armed force of King Richard II’s men, under Thomas of Woodstock, the Earl of Buckingham, and Sir Thomas Percy, charged over the dew from the north-west as expected and, in one shock attack, broke through the unguarded entrenchments, smashed the flimsy barricades, and began to slaughter the men of Essex. To avoid being ridden down, the likely route of the King’s foot-soldiers (archers and men-at-arms) would have been to charge across the heathland to the north-east of the camp. The Essex peasants were no match for war-horses and men-at-arms with spears, axes, and swords. Undisciplined, they broke their barely-formed ranks and the battle became little more than a rout. Some stood and were cut down. Many fled into the wood and were hunted down. Some grouped themselves into the old East Saxon fighting-rings and made an orderly retreat towards Ramsden Heath, beating off their attackers, picking up stragglers, and retiring like true soldiers. The King’s men killed some 500 Essexmen; many were buried in the churchyard at Great Burstead (there is a persistent, long-standing tradition that Wat Tyler is also buried there). All the horses (over eight hundred of them) were captured.

The remaining rebels fled to Colchester where they tried in vain to persuade the people to support them and to close the town-gates. Then they fled to Sudbury hoping to join up with the men of Suffolk; instead they found the county already pacified and royal forces attacked and routed them. The survivors went off to Huntingdon where they were also chased off. The last band made a stand at Ramsey Abbey where twenty-five were slain and the rest dispersed, becoming outlaws and remaining at large for a long time.

The King’s armies then moved systematically through Essex dealing with local resistance and settling debts as they went. At Chelmsford and Colchester it is recorded that men were sentenced to death in batches and, in the streets of Essex towns, disembowelling and hanging continued briskly. As many as nineteen victims were seen hanging from a single beam in one street; others were half-hanged at one street corner after another, before being mercifully despatched after the fourth or fifth occasion. Billericay men involved in the Revolt included an anonymous ‘certain weaver from Billericay’ who took part in the attack in Brentwood on 30th May 1381, Thomas Plomer (beheaded on 26th June for his part in the Revolt), Roger Forster known as Roger Underwode (whom the peasants had freed from Marshalsea Prison in London on 12th June) and Walter Cartere. The last two were both outlawed on 4th July 1381; their fate is unknown…but there must have been many more local rebels whose names are unknown to history.

The site of the battle has never been the subject of an archaeological survey. Among the written recollections of Edith Sparvel-Bayly, who in the 1880s lived with her father, the historian John Anthony Sparvel-Bayly F.S.A., at Burghstead Lodge, is a recollection of her father conducting excavations near Norsey Wood and finding some “relics” of the “fight…between Wat Tyler’s party and the King’s men”. Among these were “coins of Richard II’s time and bits of old harness”. Unfortunately, there was no indication of exactly where the finds took place or what happened to them.3 Many years ago some chainmail links were found in the rear of a Norsey Road garden and are now in The Cater Museum. In 2014 in the rear of my garden in Martingale Road I found a buckle from the last quarter of the fourteenth-century. In July 2017, not a yard away, out of the earth came a Richard II silver penny from the first die of the York Mint dating from 1377.

These finds came from present-day, built-up areas. The wedge of heathland between Goatsmoor Lane and Potash Road (over which the King’s foot-soldiers charged) is pristine as is the land to the east of The Vale running behind Potash Road (over which the King’s knights rode). So too is the land adjacent to Coxes Farm Road (over which the Peasants were hunted down as they fled south once out of Norsey Wood). The archaeology will have lain undisturbed and intact for 639 years.

These three areas are designated under the Basildon Council’s Local Plan as land suitable for housebuilding. The struggles of 1381 and 2020 have many common features: Government-backed, local officialdom seeking to exceed its authority (whilst claiming to act in the name of the Law) and to impose its will on an unwilling majority of the people; a pretence at consultation and conciliation in the face of opposition such that legitimate concerns can be raised but then, with supreme arrogance, dismissed or ignored; an opposition with no experienced political figurehead, obliged to fall back on its own resources, local initiative, and brave individuals willing (literally) to raise their heads above the parapet. The only things missing are the pitchforks.

England might well have become a better land for its people had the peasants won in 1381. But they did not win, yet the effort itself was no failure. Their cause has remained part of England’s heritage; its impetus swept on through every phase of our history, for the cause of freedom is a living cause; it is the flame that can be smothered but not extinguished. And we should rightly be proud of the part Billericay played in it. Perhaps too, there is a lesson to be learnt by us, the inheritors of that flame, in 2020.

1 Historia Anglicana, by Thomas Walsingham Quondam Monachi S Albani, HA, ed. by H. T. Riley (Rolls Series, 1863-4, 2 vols.), pp. 18-19; The Westminster Chronicle 1381-94, attrib. to Robert of Reading, ed. by L. C. Hector and B. F. Harvey (Oxford, 1982), pp. 12-18.

2 Despite the pretensions of a country park in Basildon there is not one scrap of evidence to suggest that Tyler came from that village, as it then was. There are though historical references to his having come from Dartford, Deptford, Maidstone, and Colchester. He certainly led the rebellion from Kent.

3 From Edith Sparvel-Bayly’s memoir, Yesterday – A Childhood in Billericay. I am grateful to Katie Wilkie, Curator of the Cater Museum for this information.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page